In May 1843, Charles Dickens was invited to a fundraising dinner in aid of the Charterhouse Square infirmary, which cared for elderly, impoverished men. Ironically, most of the diners were very wealthy men, who made fortunes in the City of London. Dickens wrote a contemptuous letter to his friend Douglas Jerrold describing them as “sleek, slobbering, bow-paunched, overfed, apoplectic, snorting cattle.

The author was burning with desire to bring about genuine changes to society. He was “stricken down” by reading the 1843 parliamentary report on Britain’s child labourers, written by pioneering doctor Thomas Southwood Smith and intended to write a pamphlet titled An Appeal to the People of England, on Behalf of the Poor Man’s Child, “with my name attached, of course”. The more he thought about it, however, the less impact he felt it would have. Instead, he wanted to write something that would grab people’s attention, something to strike “a sledgehammer blow” on behalf of poor children and have “twenty thousand times the force” of a government pamphlet.

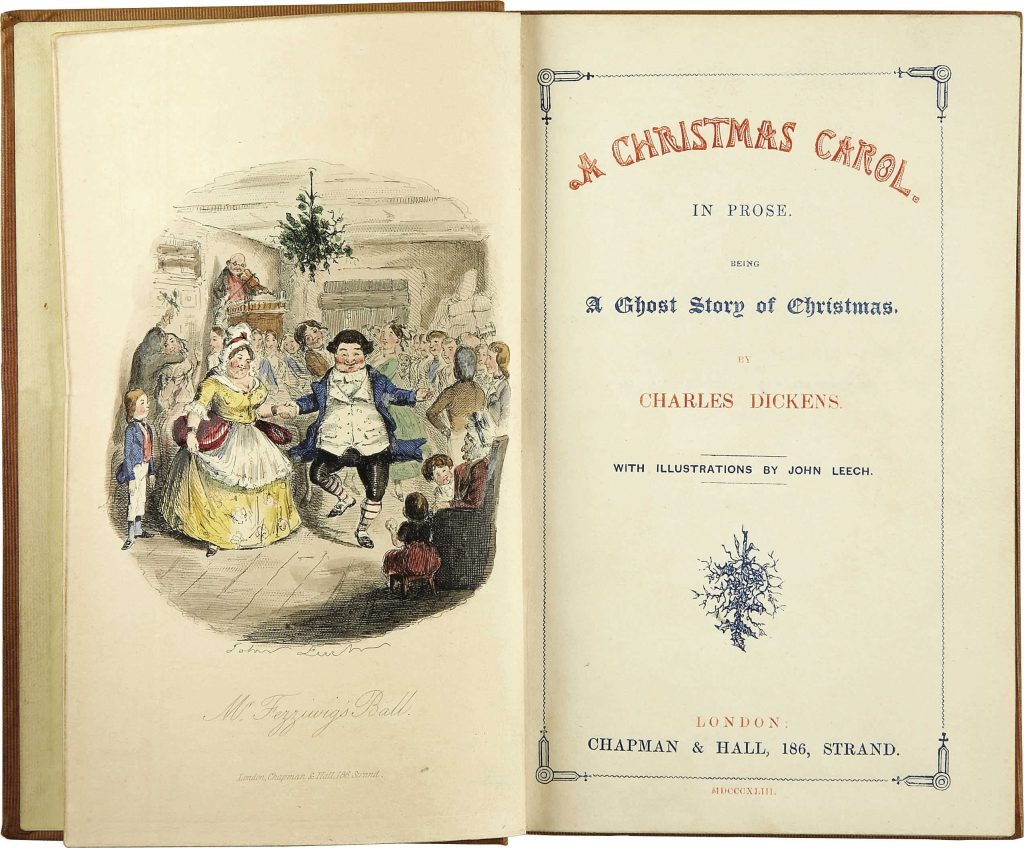

In October 1843, Dickens travelled to Manchester to give a speech in support of the Athenaeum, an educational charity for working men and women. His older sister, Fanny, lived in Manchester with her husband, Henry Burnett, and their two sons, Harry and Charles. When Dickens visited them, he was confronted by the difficulties facing his disabled nephew Harry. It made him think about the realities of what life was like for impoverished disabled children, whose lives were even harder than those of their able-bodied siblings. Harry was the inspiration for Tiny Tim. (Sadly, unlike his fictional counterpart, Harry Burnett did not survive – despite his uncle’s best efforts to pay doctors to save him.) […]

First published on BBC Culture on 22nd December 2017. Read full article online.